Paul Murray does something completely remarkable this week and presents some criticism of state political and social decisions that could almost be considered legitimate. While his take on the issues is rather typically unreasonable, biased and full of rhetorical trickery, I think its more important to cover something the story that the West ran on the front page and then again on pages 8-9: ‘”Revealed: United front on radical green laws; No positives in it for us’

In this piece the West Australian provides a platform for the WA Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Business Council of Australia, National Farmers Federation, the Chamber of Minerals and Energy (WA) and the Association of Mining and Exploration Companies to vent their spleens about the potential problems further environmental regulation could produce for them and their members.

In the interests of balance, after 16 paragraphs of mineral and oil extractors complaining about this possibility, there is a single paragraph from the Australian Conservation Foundation stating ‘we need a national EPA to get the politics out of decision making, to be independent and make independent decisions on the facts to ensure nature is protected’. Doesn’t seem unreasonable.

But of particular concern, the article asserts, is ‘the looming threat of a Greens backed ‘climate trigger’ being shoe-horned into the environmental reforms. A climate trigger means all projects estimated to produce more than 100,000 tonnes of Greenhouse gas emissions a year would need a special exemption from the environment minister’.

This is presented to the reader as though such a requirement is an abhorrent incursion on business and industry in the state. Instead, let’s suggest that the emission of 100,000 tonnes of Greenhouse Gas PER YEAR is actually a significant public risk that needs to be addressed as an environmental threat.

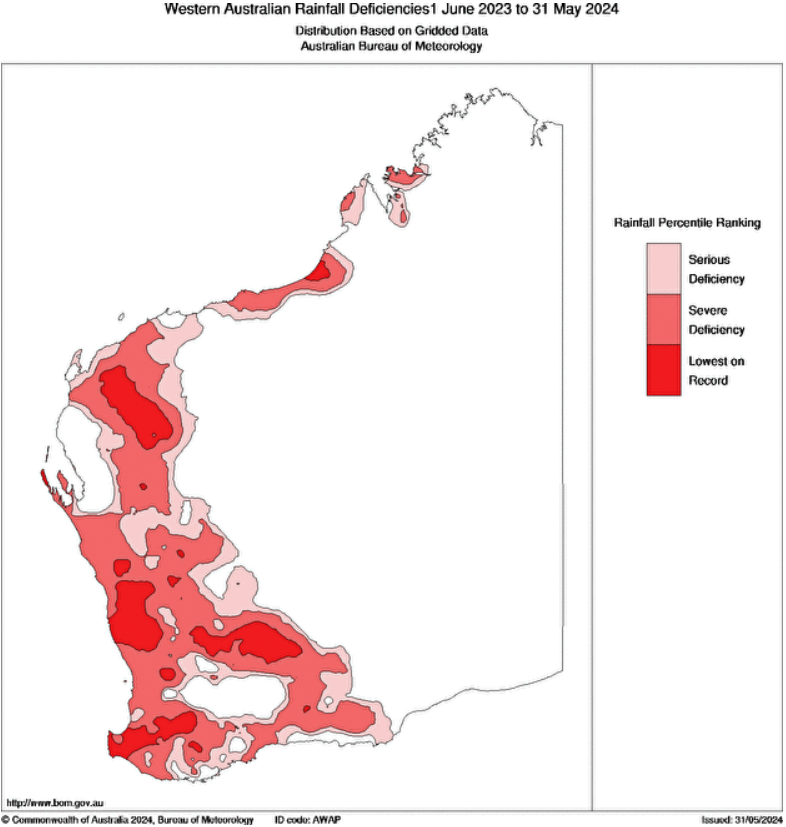

For those not keeping up with science, or still maintaining a belief that climate change isn’t real, it’s worth pointing out that the last 12 months have been the hottest 12 months ever recorded . While the threat of climate change can seem vague and hard to define, this heat has accompanied a severe drying trend in Western Australia, as can be witnessed by this rainfall data from the past year:

In terms of what this data means to how we live, this lack of rainfall is threatening the ongoing viability of our Southern Forests. It’s also threatening the viability of farmland all over the southwest.

What annoys me about the West’s coverage of the issue is that there is really no attention given to the argument for regulating heavy carbon-emitting industries, even though there is clearly a public need to do so. Instead they insist, there is ‘nothing in it for us’.

More importantly, there is also no attention given to the intended outcome of Albanese’s environmental policies – that as a nation we should use the need to pivot to cleaner and greener industries and forms of production to stimulate jobs and economic growth. This is what we need to do. Not only because that’s the best way to create a more egalitarian economy, but also because the cost of greening industry and services is a lot cheaper than trying to irrigate our southwest because it doesn’t rain there anymore.

In short, there are a lot of positives in environmental regulation for ‘us’. But when the West says ‘there are no positives in it for us’, they really mean there’s nothing in it for the mining and gas businesses the West owns.